A Hole in the Bucket by John J. Staughton

SHASA SLAPPED AT HER CHEEK, the tickling flutter of a blowfly on her eyelid wrenching her from troubled dreams. Her skin was already sticky with dried sweat from the early morning heat. She lay for a few selfish moments with her eyes squeezed tight, her head cradled uncomfortably between the loose straps of her cot. The malaise of the wanjala heat rested on her chest like a sack of maize.

Her mind whirred into action, though her body desired nothing but stillness and peace. She had once again dreamt of a house at the base of the mountain – with big windows and clean orange bricks, a tiled floor, and water flowing from shiny pipes. Holding her eyes shut, she lived in that world for a final moment.

When she opened them, the scene she took in was simple and familiar – the shuffling lumps of her three children in the small cots across the room and the line of ancient pots and dusty bowls on a crooked shelf on the wall furthest from her bed. She sighed as her eyes fell on the four buckets placed carefully next to the door. Two were large, orange plastic pails, large enough for her youngest son to sit in. Her neighbor’s daughter had found the plastic buckets and generously given them to Shasa. The other two were large metallic things, like oversized lampshades drowned in bullet silver, discolored and dented from top to bottom.

Shasa had begun calling them sabuni and supu, because one type held the water used for washing and cleaning (soap/sabuni), while the other type was used for cooking and drinking (soup/supu). Shasa pushed herself to a seated position, instinctively reaching for her back, which seared in protest against movement of any kind. She slipped her feet into the worn sandals beside her bed and pushed down on her knees as she hoisted herself to stand.

Spontaneity was no longer a part of her reality, and had not been for more than a year. When the family donkey fell ill and died, Shasa knew that it signaled the end of what little freedom she’d gathered in a pile since the third child was born and her husband was killed. Her days marched on in the static pattern of survival, with thoughts and breath borne of need.

She shuffled to one of the metal buckets and looked inside, barely illumined by the dim glow of the morning. A few bugs, no more or less than usual, drowned or fluttered in the shallow puddle that remained. Shasa cupped her palms and scooped out a tepid handful, which she sipped gently from, and then tossed onto her parched face. It was a shock to her system, warm as it was, and it washed the final groping strands of sleep from her eyes.

There was some ugali left in a pot that her daughter had prepared the evening before. Shasa trudged to the detached kitchen off the back of the house and assembled a few pieces of kindling beneath the charred memory of the last fire. Her practiced hands coaxed the flame to life to heat the cornmeal porridge that would feed all four of them for the day.

Their living space was small, and she knew that even with her nearly silent, practiced movements, some shift in the air would disturb one of the children, and the other two would follow soon after.

Bakari was typically the first to rise, often before dawn, within moments of Shasa’s first tired rumblings. Shasa teased that Bakari’s uncanny hearing was due to the size of her ears. She had called her daughter tembo kidogo since birth, and though Bakari blushed and hollered when Shasa used the term of endearment, meaning little elephant, her daughter secretly adored the name.

Bakari’s two younger brothers, Hamidi and Hadiya, were irascible young boys of 4 and 6, always getting into trouble, but tiring themselves out by late afternoon, the pangs in their hollow stomachs often sapping their exuberance. Shasa saw none of this, but was told of her son’s daily antics by her elderly neighbor, who spent most days sitting outside her corrugated shack, tending to and lightly sweeping backhands at the small gaggle of grandchildren she guarded.

She boiled a fresh pot of orange bucket water over the coals, which sputtered pitifully. A groaning yawn from a son behind her meant that the day would soon begin, and she would be out the door. Shasa surreptitiously glanced to her yolk leaning crooked behind the buckets, and the twinge in her shoulder ached in knowing reply.

“Habari za asubuhi, Bakari.” Shasa wished that her voice held more force, something to reflect excitement for the day ahead, but it sounded flat to her ears.

“Good morning, mother.”

Shasa’s neighbor never mentioned Bakari playing with the other children; the slender girl was quiet and composed, much older in spirit than years. She effortlessly learned the tasks of the home and pursued her studies diligently, but never eagerly, as though she understood that her time in the classroom would soon come to an end.

“It is time for me to go, tembo kidogo,” Shasa said, continuing to stir the porridge as the stove heated up. “Can you make sure your brothers eat?”

“Yes, mother, but I want to go with you. May I come today?”

“No, Bakari, not today. You do not want to go with me. Mind your brothers. Be a good girl. I will see you later.”

“Yes, mother. But when will I come with you?”

Bakari was naturally curious, which was inspiring to Shasa, but Bakari’s desire to literally follow in Shasa’s footsteps was heartbreaking.

“When, child? Hopefully never. At least, not for many more months.”

Shasa kissed Bakari lightly on the head and turned away. She reached for a kanga that she had hand-washed the night before, enjoying the stretch of her muscles as she raised her arms over her head. Their sparsely furnished home left no room for privacy, nor was there time to worry about modesty. She heard a ripple of small cracks from her lower back, and a painful tension that she hadn’t noticed suddenly disappeared.

Shasa hurriedly spooned a few mouthfuls of the porridge straight from the pot, to which Bakari said nothing, but there was precocious concern in her young eyes – something Shasa had seen many times before.

“Goodbye, little one. I will be home later.”

“Goodbye, mother.”

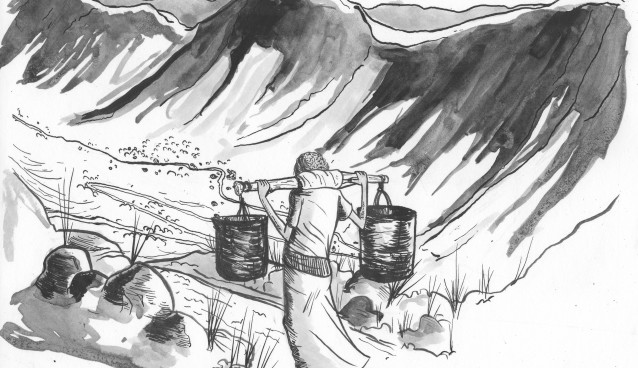

Shasa walked towards the door and picked up the wooden yolk leaning against the wall. The smooth staff had two strands of rope looped through holes in either end, which she expertly tied around the handles of two buckets – one orange and one metal.

Taking a final look at Bakari, who was shuffling back towards the fire, and at her two young sons, still squirming lazily on the cot they shared, Shasa stepped into the morning.

*****

Though it was early, the sun was already baking the thirsty ground beneath her feet, and she could hear the crunch of dehydrated earth. Shasa paused outside her home and leaned against the corrugated panels that had been hastily patched together, feeling them give slightly under her weight. She adjusted her sandal strap, which threatened to snap at any moment – a few more weeks, at most.

Looking down the dusty lane between other ramshackle shanties much like her own, she noticed that few of her neighbors were awake. Or perhaps they have already started the journey, Shasa thought to herself.

The yolk was balanced on her right shoulder – the stronger of the two – for the first half of the journey. She had learned years ago that her body could only take a certain amount of strain in a given day, and pain didn’t distribute evenly. The intimate knowledge of her body’s weaknesses had grown over the course of the two decades since she had first taken up the yolk under her own mother’s watchful eye.

She reached the end of her lane, a wide strip of tamped dirt parallel to a rotting trench of waste, and peered over the edge of the world. Shasa, Bakari, Hamidi and Hadiya lived near the top of the mountain, as high as abject poverty could drive them.

The winding downward path was treacherous and unmarked, and her daily destination remained far out of sight, as it would remain for hours. Hoisting the yolk and exhaling exhaustion, Shasa took an initial tentative step – the first of many thousands.

Although she took the same general route every day, crumbling soil and the shifting earth meant that she had to pay attention to every step, as a single slip could be disastrous, particularly upon her return, once the buckets attached to the wooden beam across her shoulders were full.

Pain. Basha. But another day alive, Shasa. Your children are at home, with enough food and water until you return. Step. Step. Step. Step.

The sun was not high in the sky, but it seemed to sizzle the air, making every breath unpleasant and dry, crackling the thirsty skin of her throat. She could make out the slight depressions of earlier feet, and could see small dark figures moving down the mountain ahead of her.

She measured the trek in pieces, marking her progress with landmarks and the changing angle of the sun. After a few thousand steps, the familiar tension in her thighs began to build slowly, like the kindling beneath an infant fire. She heard rustling in the underbrush beside her, and was frightened by the size of the bushes, as they could conceal an animal as easily as a man.

If you are a beast, calm yourself. If you are a man, show yourself. If you are a beast of a man, may God protect me. Step. Step. Step.

Weeks earlier, she had narrowly avoided a puff adder landing beneath her feet, leaping over the basking snake at the last moment, but receiving an aggressive hiss for her carelessness. Adders were lazy snakes, not prone to chase or follow, but their bite was deadly within minutes. For the rest of that day, her eyes had been locked on the ground, combing the dirt and sand for serpentine patterns, which meant a less careful watch for the real danger of the road.

One dry season earlier, a man she did not recognize had stepped into the path as she returned from the well. The blades of pain in her back were nearing their daily fever pitch, and she had barely enough energy to finish the climb. He had said nothing, but stood meaningfully in her way. She looked behind her for any other water-gatherers, but none were in sight. Shasa gently bent forward and lowered the yolk, careful not to spill the sloshing gold inside.

A beast of a man, but I will not die today.

As though some foul contract had been signed, the man did not touch her buckets, but he grabbed her roughly by the hair and threw her against an outcropping a few yards off the path. She had been walking for the better part of seven hours, after a sleepless night with Hadiya, who had been struck down by malaria, feverish and wailing.

“Please, I am going home to my children,” she offered meekly, appealing to any shred of humanity within the stranger.

Her instincts told her to lash out and defend herself, but the weight of her limbs was incredible, and her back slamming into the rough stone had knocked the fight from her heart. She receded into a tiny room within herself, where no one could reach her; not even her children or God himself.

He tore at her clothes, beating her around the face and neck until she lay still. She stared up into the painful blue of the sky, blinded by sweat and blood that ran from a cut on her forehead.

Do not cry. Do not give this animal any part of you.

She had not cried in many years; tears and self-pity cost time and water, resources more precious than dignity. That day, however, they welled in her eyes, which refused to look into the man’s rolling eyes and sweaty, malicious grin.

The man had cursed as he forced himself upon her, calling her samaki wafu and mwanamke kijinga, pushing one side of her face against the brittle ground. His assault was brutal and fueled by anger, and when he finished his violation, he kicked her once more in the ribs and stepped back into the road. Lifting one of the heavy buckets to his mouth, he drank deeply, carelessly spilling water onto his chest and the ground, which hungrily swallowed it.

As he disappeared into the brush down the mountain slope, Shasa pulled herself to a sitting position and carefully brushed the dirt from her open wounds, trying to wrap the torn fabric modestly around her. He had not stolen her water, only wasted some, and for that, she nearly felt grateful. She allowed the tears to come once the man was out of sight, and she leaned over a bucket, weeping salt into the pools.

Humanity is a luxury, but water is life. Even monsters know that.

Shaking the memory from her mind, Shasa forgot the rustling bush after distancing herself by another twenty paces. The path began to level out near the bottom of the mountain, and the angle of the sun told her she had been walking for nearly three hours. She was not moving any faster or slower than usual – years of repetition had instilled clockwork efficiency to her steps.

She passed a small collection of homes on a small plateau near the base of the mountain; they were far from luxurious, but the walls were made of thick wood and showed few cracks; some even had cement foundations. Small groups of people outside their homes watched her progress; she made eye contact, but offered no words of greeting.

The chasm of experience was firmly in place, and while the tide of a single season could reverse any fortune in this fierce place, for now, their lives were on different paths. Shasa’s future had little chance of improving, although her children might have some opportunity… or perhaps her grandchildren.

Those groups of hollow-eyed observers from beside the cement homes feared the reality she represented as she passed down the mountain. They had descended to some level of comfort, living only a short walk from the well, but they knew the risks, and the dagger-edge precipice they lived upon.

The fields those families worked must have produced well, but would they continue to thrive? The escape of their wisest and strongest to better jobs in far-flung cities may have provided them with a lifeline to another future, but could that last?

The people on her descent feared Shasa more than she envied them. Unlike them, she had nowhere else to go, no more higher place to be pushed – only to the sky above.

By the time she began the final hour of her walk, the sun had already passed its zenith, angling angrily into her eyes and sending rivulets of sweat into her eyes. Shasa had caught up to a half-dozen other water-seekers, her pace faster than usual to make up for her late start. She recognized some, a few from her mountaintop community, and others from various slums and unnamed villages that sought out this well from miles around.

It had been collectively deemed the safest in the area, an imperfect belief based on fewer reported illnesses in the families nearby and blind optimism. Shasa had nursed all of her children through various sicknesses; Hadiya had survived malaria and Hamidi had nearly died of dysentery in the last wanjala – the hunger season. Bakari had thus far been lucky, a fact Shasa held in her heart with pride.

Step. Step. Step. She will not live like this. She will be more. Somehow, Bakari will escape.

Shasa’s thoughts drifted to her daughter’s day, passing the journey with imagination, rather than counting her haggard steps on the road. Bakari would have woken the boys up and made sure they ate every morsel of what little food had been set aside for the morning. The boys would give her a difficult time, but they also respected her. They would then play while she tidied the humble house.

If her chores and health allowed, she would walk the twenty minutes to the small school built against the side of the mountain, staying only a few hours before collecting the boys once again in the afternoon and taking the short trip to the local market. Shasa could see her daughter’s face clearly in her mind – the tired grimace that mirrored her mother’s far too often, a child resolved to a fate she hardly understood.

Shasa felt the hot line of pain in her left hip arriving right on cue; she never seemed able to reach the well before the ache returned. She could hear the low rumbling of gathered voices around the corner in a small square, and she breathed a small sigh of relief that she had finally arrived.

Step. Step. Nearly there. Step. Step. Halfway home.

Thoughts of her daughter disappeared as she lined up behind a few dozen women, each bearing buckets of different shapes and colors. Every vessel looked worn and beaten, having been repurposed and patched many times. Some women conversed quietly with friends or empathic acquaintances, but most conserved even the energy it would take to communicate. They had all come for the same reason, but most had many more miles to go. Regardless of where they had come from, or how long their journey had been, all were equal at the well.

Their fundamental need for water unified them. Each had the same likelihood of falling ill, should the source be tainted for one reason or another. Each had their own particular methods for protection against the vicious diseases that spread like brushfire through the body.

As Shasa neared the spigot, which drew water up from far below, she slipped the yolk from her shoulders, luxuriating in the release of weight – if only for a few moments. There was a young girl standing in front of her in line. She looked only slightly older than Bakari, but expertly handled the bucket resting atop her head – far from a novice.

No more steps. For now. She is a Bakari. She is a daughter of this place. She will learn to count her steps.

As the girl turned, her yellow bucket full, Shasa offered a maternal smile, but the child’s gaze was already turned away, focused on wherever and whomever was awaiting her liquid prize. Not wanting to delay herself or those who had joined the line behind her, she hurriedly dismissed her daughter’s doppelganger and bent to fill the buckets.

The sound of water smacking wet and thick in the buckets always rang pleasant in her ears, and for a few rushed moments, Shasa closed her eyes and imagined a bathtub filling with ice-cold water.

Shasa knew precisely how long it took for her buckets to fill during wanjala – nine even breaths – versus the faster flow in other seasons of the year. When one was filled to a few inches below the brim, leaving room for the swaying of her tired steps, she deftly switched to the second and tugged the first bucket out of the way. Each day, the speed of the water seemed to slow imperceptibly; the Earth itself was growing tired of offering its lifeblood.

One day, the Earth will abandon us. God will cleanse this land with a great flood. And no daughters will count their steps.

Shasa twisted the spigot closed and bent her neck beneath the yolk, gently unfolding her back, bracing her spine for its burden. Her muscles winced in revolt, but Shasa knew it was only temporary; numbness would soon set in. That same numbness had saved her life, and the lives of her children, more often than she cared to count.

Raising her eyes to the small crowd of women and children in the dusty square, she saw some conversing, and even laughing. Shasa had no time for such things; it was only in the line, waiting their turn for liquid salvation, that these women were equalized.

Step. Step. Hurt. Worse than yesterday? No. Pain. No… it is the same. Step. Step.

Shasa’s daily relief was the sun setting against her back on the return journey. It still brutally beat her skin, and she awkwardly pulled the back of her head wrap down to protect her neck. The yolk rolled over her shifting shoulder blade, and that small jolt sent a tiny wave of water slopping over the edge to splat on the ground, sizzling to mock her carelessness.

Steadying her gait to protect every drop that remained, Shasa retraced her steps through the small central town. She carefully trailed another water-gatherer in a blue kanga, using her wake through the sporadic crowd to move smoothly. Within a few minutes, Shasa returned to the cracked dirt of the main road, and her eyes rose to the mountain bulging in the hot hazy distance.

Step. Step. Step. Somewhere, Bakari is there, waiting for my return. Hadiya and Hamidi will be lying on their cot – exhausted, but laughing. Step. Step. And thirsty.

As the flat arid plains began to buckle and rise, she closed her eyes and offered a small prayer to the empty sky. Shasa felt the flesh at the top of her knees begin to stretch and strain, while the whisper of fire in her thighs blew to life. The bar across her shoulders was merciless. The ground seemed desperate to tug the buckets back into the dirt, threatening her steps with loose-soil stumbles and nearly-buckled knees, as though the earth was dying of thirst – not she.

Pain had become Shasa’s daily companion, as much a reminder of life as breath. Her sleep was troubled and dreamless, robbed of all feeling or passion, and she awoke to numbness in her limbs, crying mouths and empty bellies. She had been molded by pain and want for nearly three decades, alleviated only briefly by her husband, who had provided support and compassion, albeit little money. His daily bouts of drinking had grown more intense, and the swelling family had moved further up the mountain, needing more but having less.

When he was killed on the road, likely drunk, he had been robbed of his scant possessions and rolled into a brush-covered ditch. His body had been found days later – by the smell – and it took another two days to identify who he was and where his family could be found. He had been missing for nearly a week before the authorities made the trek up the mountain to bluntly inform her that he had been killed. The façade of an investigation lasted only a day, and then her life – as well as the fate of her children – was irreparably decided.

Step. Pain. Step. Hurt. Step. You have not had a drink of water yet. You have not stumbled. You are on the mountain. Pain. Home is getting closer. Step. Step. Step.

Passing the low-lying mountain communities, she saw different faces and eyes than those that had studied her earlier. Shasa detected a difference in their expression as well – a shift from pity to admiration. She carried unusually large buckets, the excess from each day gradually adding up, allowing her one day of freedom in ten.

Although every twist of the mountain path seemed anonymous and identical to the one before, Shasa felt a deep sickness rise in her stomach when she passed the spot of her attack. The pain in her shoulders faded momentarily, masked by adrenaline and nausea, and her steps sped up to quickly overtake the past.

That unforgettable landmark meant she was only two hours from home. Glancing back into the weakening sun, Shasa consciously hastened her pace, eager to return and enjoy some small sliver of daylight with her children. Her stomach roiled furiously, and the promise of fresh ugali, a simple dish Bakari was becoming quite proficient at preparing, urged her along.

Step. Step. Bakari will be cooking, and the boys will run to meet me at the door. I will scold them, and warn them not to spill the water. Step. Step.

The three children awaiting her had cemented her purpose after her husband had been killed. They had saved her life, just as she saved theirs every day on the savage slope of the mountain.

The final hour of her treacherous hike was always the most difficult, and while her heart tried to pump more blood and energy into the splintering muscles of her back, starved with the desire for home, the frail human cage of her body refused those demands.

When the final cresting rise appeared, it was all she could do but run towards it, yet any pace beyond a careful shuffle would eradicate all that she had just struggled to do. The contents of the buckets on either end of her yolk were more precious than her children in those last pitiless steps; they were the drops of her blood, Christ-like in their transmutation to water – the beam she bore on her back more damning than the cross on his.

Step. Step. Pain. Basha. Step. Home. Hurt. Pain. Step. Hunger. Step. Home. Water. Step. Water. Step.

“Mama! Mama!” The cries of Hamidi and Hadiya pierced the haze of dust and sweat in her blurred eyes; they ran towards her, their feet sending up puffs of brown that swirled in the sun’s final, blazing rays.

The boys halted a few feet from her, young and wild, but keenly aware of the seriousness of her task – the daily labor that took her away from them.

“Hodi mtoto,” she greeted them with a sincere smile, but even the young boys could see the grimace in her eyes. She slowly squatted down, hearing both of her knees crack violently before the buckets came to rest on the ground. Hamidi, the older of the two, walked cautiously towards one of the buckets, but Shasa waved him away. Instead, once she eased the yolk from the jagged range of her shoulders, she gathered her sons in an embrace.

Shasa looked up to see Bakari walking slowly towards them, an emotionless expression on her face.

Such a beautiful girl. And my happy little boys. They will be men someday. She will be a woman, but not like me. No more steps.

“Welcome home, Mama,” Bakari began, rubbing Hadiya’s short, coarse hair affectionately. Without being asked, Bakari bent to the yolk, expertly loosening the knotted rope and then lifting the orange bucket. Shasa could see the tendons flex in her thin legs as they strained against the weight of the water.

“Boil that,” Shasa cautioned unnecessarily; Bakari knew the risks. She had seen both of her brothers grapple with death in the past two years. Bakari did not respond, but Shasa knew that she had heard.

Bakari slowly hobbled back to the dilapidated shelter of wood, scrap, and aluminum siding they called home. Shasa untied the second rope and the boys dutifully lifted the yolk between them, one at each end, and trailed after their sister. Shasa pressed her hands to the ground and hung her head. She drew her fingers into a fist, and felt the powdered earth cracking and lodging beneath her nails.

She crouched there for a moment, feeling every lancing throb of pain, from her numb toes to the tight aching behind her eyes. She watched the boys disappear into their home, less than fifty paces away, and she mustered a final surge of strength. Pushing to her feet, Shasa scooped a final splash of energy from the exhausted puddle of her bones. She bent down to lift the second bucket, and awkwardly waddled the final leg of her daily journey.

Step. Almost there. Pain. Step. Almost done. Thirsty. Step. Hungry. Step. Step. Pain.

Home.

Bakari had wasted no time, and from the doorway, Shasa saw her daughter carrying a half-full metal bucket to the fire in the kitchen area adjacent to their house. It would take fifteen minutes or more for the water to boil, and then another thirty minutes to prepare the cornmeal porridge; Shasa hoped that her daughter had remembered everything they needed from the market. The boys had leaned the yolk against the wall, and now sat on their cot, licking their lips in anticipation of a meal.

Shasa set the bucket down, grunting as it finally arrived, safe and sound, near the center of her home. She lay back on her own cot, patiently analyzing every part of her body piece by piece, mentally noting where it hurt more than usual, and what muscles only ached, rather than burned.

Any moments of idle thought were rarely spent on herself. Even in the silent respite her children allowed her each evening after she returned, Shasa only considered their needs. Where there had once been dreams and aspirations, or hope for the future, there was now an instinctual focus on the moments lined up directly before her.

Wash Hamidi’s clothes. Breathe. Work on sewing for neighbor. Eat. Boil more water for baths. Sleep. Boil more water for morning.

Her dreams consisted of bigger buckets, shorter mountains, and cloudier skies. Her aspiration was survival. Within her chest, Shasa felt her heartbeat slow, and her meandering thoughts began to expand in weight and depth. A phantom of exhaustion was crawling across the dirt floor and creeping into her limbs.

She could no longer feel the cuts and bruises on her hands and feet; the vise on her throat felt lessened, but not yet gone. Shasa no longer carried the weight of their worlds on her back, and the dense blanket of sleep began to enfold her.

She had always assumed that sleep and death were much the same, but sleep was an elusive luxury, and always ended far too soon. Shasa hoped that death would be longer, and better, than her life of dreamless slumber.

Step. Step. Step.

***

Find more tragic and beautiful tales in SN6: MAYDAY – available on Amazon!