Teaching With Depression by Laura Koroski

WE WERE AT A DINGY DINER in a western border town of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula when I failed to save my camper.

It felt like I was trapped, or frozen. For all my training, I couldn’t seem to respond to the panicked shouts of “She’s choking! She’s choking!” that flew from the mouth of her friend.

I was just beginning to stand up when Sean reached her. “I got this, I got this,” he said calmly, and performed a textbook Heimlich. A piece of meatloaf flew out and she sputtered, regaining her breath. The whole table started breathing normally again.

Sean and I left the kids alone long enough to walk out into the parking lot and call our boss. Amanda Parker has a calm expertise about her; she deals with emergencies in the same matter-of-fact way that she does when displaying the camp’s Lost and Found. I heard no alarm in her voice as she assessed our handling of the situation, only caution. Our camper was alive and safe. We had dealt with an unpredictable situation and done well.

Or so I thought, until Amanda asked how the rest of the day had gone. Sean hesitated. “It’s been a long day,” he said. “These kids really try our patience.” He paused. “Well, they try Laura’s patience.”

I looked away, struggling to not say something cutting in return. Whose patience wouldn’t they try? Well, Sean’s. Somehow, he won the award for the chillest guy on the planet, and the innumerable pranks, bickering, singing, health problems, misbehavior, and general high-need nature of spending 10 hours in a van with this group of preteens hadn’t bugged him. It made him great at this job, and I should have loved that. But instead it made me despise him and resent my own inability to stay perfectly relaxed.

Sean passed the phone to me.

“Laura, is that true?” Amanda asked.

I swallowed. “Yeah.” I wished I didn’t have to admit it. “I’m kinda stressed.” I should have left the qualifier out, but I had to keep my pride somehow.

Amanda saw through it anyway. “Those kids are really difficult. But they’re your responsibility.” I winced at the implied accusation. “Short of taking them back to camp, you’ve got no other options.”

Sean spoke up. “Tomorrow, we’re taking these kids into the backcountry. I need to know that we’re both in this together. I can’t lead this trip by myself. I need to know that when you get stressed, or when they push your patience, you won’t shut down.”

It felt like a slap in the face. I wanted to protest, to say that I didn’t shut down, but I couldn’t deny that I had cried earlier, or that I was crying now. My tears were a sign of my frustration, but the rest of the world saw them as a weakness.

“You need to work as a team,” Amanda said. “Otherwise, this trip ends.” The shame inherent in her ultimatum was inconceivable.

“Can you promise me you won’t shut down?” Sean pressed.

I wiped away some of the tears, staring down the remote road. “I can try.”

“That’s not good enough.” Amanda’s voice was no longer reassuring, but forbidding. “You need to do it. We need to know that you’ll do it.”

I felt anger rise up in me. My efforts weren’t good enough? All the growth I’d made, all the progress I’d achieved, all the gains I’d had over the years as a leader—it was all for nothing now? As long as I wasn’t as chill as Sean, I was doing it wrong. And of course, there was no way I could guarantee that I wouldn’t fall apart again.

But I couldn’t say any of that. There was only one option if I wanted to keep the job that I loved, at my favorite place in the world, and not live a life of shame.

“I’ll do it,” I said. It was a lie, but maybe if I said it loud enough, I would believe it. “I won’t shut down.”

***

Long before I ever stepped into a classroom, I loved being with kids in their wildest moments. Those moments were called summer camp, and they were some of the best of my life.

They were also some of the hardest. I had always been a sensitive and quiet child, and struggled to make friends in large groups. Over the years, camp helped me come out of my shell—but I was still myself. I loved large groups for their energy, but preferred quieter settings where I could really bond and get to know people.

So much of my teenage and college years were shaped by the place, the people, and the challenges I encountered at camp. Yet I felt like I was being told to conform to a certain personality type—loud, overly confident and very chill—and I resented it. No matter how much I grew or changed, I would never become that person.

That phone call from the Upper Peninsula was not the first time I was told, “Just don’t get so stressed,” nor would it be the last. Not a single time was it helpful. From a clinical standpoint, telling someone who is stressed or anxious to chill out is like telling someone who’s just been shot to stop bleeding. It’s laughable. It conveys the impression that the person wants to be anxious, or depressed, or bleeding. It suggests there’s a choice in the matter and as soon as you tell them to snap out of it, they’ll immediately become calm, return to happiness, or stop bleeding to death.

The tragic thing is that those good intentions really do pave the road to hell. At least, they did for me. The real hell would come a year after that call.

Some people can point to an incident, an event, a reason for their depression. I couldn’t. I’d finished my first year of grad school, an intense masters program in teaching history. My life was pretty good. So why did I spend my days crying?

I tried to immerse myself in the books and movies I loved, but they only distracted me temporarily. I tried to schedule social events, but when I occasionally saw friends, I found I couldn’t connect with them. I was hungry, but ate very little. Sleeping was hard, but getting out of bed was harder.

In other words, I was a classic case of depression.

It was never consistent for me. Some days were fine, others I was miserable, and I never could predict how they would go. The one thing that was consistent was the few hours a week when I wasn’t depressed—when I taught swim lessons. For that, I had to be cheerful and energetic, playful and loud. I worried constantly that I would be lost in my own head while I was supposed to be responsible for kids in the water. But time after time, for those few hours when I had to put on a mask of happiness, I could, and I did.

Yet the mask was just that—a mask—and I had trouble sustaining it as soon as my job was done. With so much time spent alone, I had nothing and no one to contrast my moods against. I struggled to recall a time when I was happy, or to foresee happiness in the future. As far as I could remember, things had always been this way. It wasn’t until my mom pointed out to me that I sounded nothing like myself that I realized what my own life had become.

For so many people, admitting a mental health issue and then seeking care is a difficult endeavor. But it wasn’t for me. I knew that something was fundamentally wrong and I needed help to put it right. Getting the treatment I needed turned out to be the hard part. It was then that the system failed me. Over the next few months, I would stumble through the offices of three different therapists, glad to talk to someone who didn’t think I was crazy, but never feeling like they had any answers for me. I didn’t have a good connection with any of them. It never seemed like they were saying much that made me feel fundamentally better when leaving the sessions. In fact, I often felt worse.

My memory of the latter half of that summer is very hazy, a blur of days spent in the deep dark hole of my mind. I returned to my second year of grad school, relieved I would finally have all the comforting things I missed about my program. I expected to thrive. I thought the depression would go away.

Instead, I struggled to keep my schedule and do my own assignments. The cohort I had felt so close to in May had changed, and those friends I hadn’t seen in months now seemed to have no place or need for me. The friendly question, “How was your summer?” had no substantial answer I felt I could give. The standard greeting, “How are you doing?” felt like a minefield where I was just supposed to lie and say I was fine in order to keep the conversation light and positive.

No one wanted to hear that I was depressed or anxious—they never knew what to say. Each time that I admitted it, I was desperate to gain understanding, comfort, relief and help. Instead, I felt judged and misunderstood. I was met with awkward silences, hasty changes of conversation, and meaningless platitudes. Each response left me more discouraged, more convinced I was a failure, more sure that everything was wrong, and more certain nothing could ever fix it.

On another night of desperation, tears and despair, I opened a new tab in Google. Can you teach with depression, I typed.

The results were not promising. They ranged from statistics on how the profession has a high rate of mental illnesses to self-help articles on how to boost yourself after a bad day. None of it matched my situation. None of it made me feel any better. But if every result hurt a bit, Jesse Scaccia’s post at the blog Teacher, Revised cut the worst:

“As a teacher, you are not allowed to get depressed.

“There is too much work to be done. The kids feast on any perceived weakness, especially in a new teacher. Or, the kids take it personally, and think you’re upset with them. Being depressed can make it seem like you don’t believe in the lesson, the school, the education system itself, and if you don’t believe in those things, there’s no way the students will…

“It’s a horrible catch-22: being a teacher, you’re not allowed to be depressed, but the emotional output required by the job makes you more likely to be depressed.

“Is there any way out of this mess?”

It didn’t matter that the article eventually ended on a helpful note. The answer to the rhetorical question was clear: No.

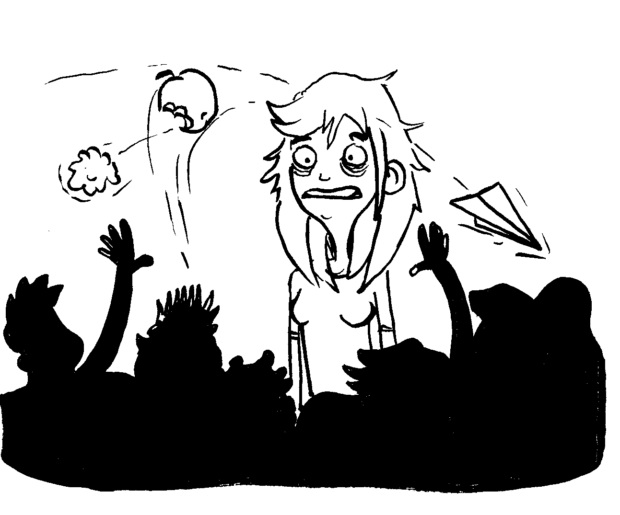

It was a crushing answer. I felt helpless, prevented from doing the one thing I really wanted by feelings I couldn’t control. It was an utter denial – the same slap in the face that Amanda and Sean’s demands had been a year before. This time, the anxiety was too overwhelming, the depression too great. I couldn’t lie and play it off.

Healthy, sane people don’t fantasize about killing themselves. I certainly never imagined I would. I had big dreams and aspirations. I had people I loved and things I enjoyed, but at that time, I was not a healthy, sane person. Depression had erased everything. I endured an evening of panic attacks, struggling to stop sobbing, to keep breathing, and to keep living. I remembered the sleeping pills and realized that it would be so much less painful to let it all end.

But I scared myself too much. I was tired of living, but also terrified of dying. I hated myself, but was also afraid of the person I had become. I called a faraway friend and managed to admit it, despite my shame. The pills were disposed of. I didn’t die that night.

Instead, I was sent to a mental health center. They assigned me to start the intensive outpatient program for depression and anxiety. Very gradually, ten hours of therapy a week began to give me skills and support to help deal with the pain, the fear, and the darkness. I met people who knew what my reality was like. They didn’t need to ask obvious questions and never judged me when I struggled. I met a cadre of counselors who appreciated my struggle, and finally had a therapist I felt I could trust.

The routine time, which had felt like an impossible commitment, came to ground me. Gradually, I regained parts of myself I hadn’t even realized were missing—like creativity—and felt emotions I hadn’t known for months—like hope.

Not to say that therapy was easy—because it never was. On the good days, it meant showing everyone in the room my most vulnerable side. On the bad days, I didn’t care about being vulnerable—I just wanted the darkness to go away. However, by looking so closely, going so deep, and paying so much attention to how my thoughts turned into emotions, I began to understand. I haltingly learned to speak the language of mindfulness the therapists practiced with such fluency. I began to feel that I had some control over my behavior. For the first time in months, I could imagine a time when I wouldn’t be depressed.

In the midst of all this, I was getting closer and closer to teaching. I spent every Tuesday doing an internship at a neighborhood high school. I alternated between classes of sharp IB seniors questioning the status quo to bored freshmen struggling to figure out the main idea of a text. It felt like traveling between different planets. It was exhausting, challenging, and led me to question many of the things I thought I knew.

But it was never depressing. Those Tuesdays were difficult, but they were struggles of physical exhaustion and energy, not with my mood. They were struggles of reaching students with special needs, modifying for Spanish speakers, and pacing myself before the bell rang. Merely observing a class felt pointless, but as soon as I got up and began asking students how they were doing, I felt purposeful. I had a role, a place, a reason.

It was on the days when I wasn’t teaching that things were harder. Time when no one required my presence and my effort was the time that I struggled.

I recognized the sense of purpose I felt when teaching, yet my mind couldn’t help but return to the article that told me I couldn’t work in those classrooms, that I couldn’t handle those lessons and that I couldn’t teach those students.

So I was incredibly surprised when I finished guiding freshmen through my first independent lesson and my supervising professor said to me, “That was the best lesson I’ve seen this semester.”

I blinked. I was sure there was a mistake. “It was?”

“Of course,” she said. “Your lesson plan was straightforward and well thought-out. You did a terrific job of engaging the students by drawing on their prior knowledge and they responded really well, right?” She looked at me, and I slowly nodded. “You guided them through the beginning of the reading, modeling how to fill in the graphic organizer. You modified the reading and assessment for the English language learner. And you changed the grouping of students to better suit their mood.”

As she ticked off each point, I waited for the blow to fall, sure there had to be some mistake. I expected the hurt to come from somewhere. Depression had taught me to do that. But this time, it didn’t come.

Instead, she said, “So that’s my quick assessment. But I won’t be following you every day of your teaching career. So tell me—how do you think you did?”

With some shock, I realized that she was right. I drew on students’ experiences on a basic, personal level. I took them at face value, and gave them the support and attention they needed. I sat there for a long moment with my mouth open, running over the past 45 minutes, looking for flaws.

“I think I did well,” I finally said. “I think all your comments were absolutely right. And that’s kind of astonishing me right now.”

That day, I left the building with one powerful thought resounding through my mind: Maybe I can actually do this.

It was that thought that brought me to the below-zero January day when I began my student teaching. It became clear within a few hours of walking into Paulson High School that it would be a place of exceptions. It was underfunded in ways typical of an urban school, but had smaller class sizes and more electives than most. It had achieved a true racial diversity that matched the population of the city—a rare, unheard-of statistic in a highly segregated school system.

My cooperating teacher, Julia, was a wonderful mentor. She was always willing to answer questions, flexible enough to let me direct my own curriculum, and friendly enough to treat me as an equal. Under her guidance, I gradually began to learn about the school and my students.

The first thing I learned was that I was not prepared for what I was about to do. I started the day with a class of twenty-five students, sixteen of whom had special needs. Those needs ranged from learning disabilities and minor hearing loss—which I had expected—to nonverbal and handicapped, Down syndrome, and autism spectrum—to which I had hardly been exposed. The students who didn’t have special needs struggled, but were far less likely to ask for help. They were also far more likely to mask their difficulties by causing disturbances.

Of course, I didn’t find all of that out at once. It was one thing to read the IEPs of students. It was another thing to figure out how they actually functioned and how I could deal with them. I received no guide for the behavior of the non-special needs students, who were my more immediate challenge. Thankfully, the rest of my classes were much tamer, although still had challenges of their own.

With no experience, a thousand demands to fulfill, and no time, student teaching is the very definition of a steep learning curve. The only way to conquer it was to keep pushing against the brick wall, day after day, hoping that it would budge. The only way to measure anything was by small improvements, little bits of growth, disasters averted.

I had spent so much time hoping for a good class, a good school, a good mentor. I quickly realized that in the end, those things didn’t matter as much as I thought they would. All the aspects of my students that were less than ideal didn’t matter. Paulson was my school, my students were my students, and I had to take them as they were.

The free rein that I was given to create my own curriculum was both a blessing and a curse. It meant that I owned, knew, and cared about the lessons I taught, but it also meant that I spent six days a week scrambling to figure out what I would teach the day after tomorrow.

Planning seemed like nothing when compared to all the time I spent worrying over my authority in the classroom. The thought of not being in control was my nightmare. While the regular classes merely gossiped, side-talking in first period consisted of comments that were occasionally sexist, racist, ableist, and nearly all abusive.

“Hey Brandon! Sit your fat ass down, you n——!” Raul called across the room as Brandon strolled back to his desk after taking his time to sharpen a pencil.

Brandon whipped around. “Naw, you shut up, you Mexican!”

“Brandon, get back to the reading,” I said, stepping between the two. “Raul, you need to focus on your work and focus on making sure those words never come out of your mouth again. Got that?”

Raul leaned around me. “You call me Mexican? Least I can read. You can’t read nothin’!” I groaned internally. Usually the class stayed above calling out those with disabilities.

In the corner, Sylvia, who had the highest grade in the class, but could do far better, muttered, “Hah. None of you idiots can read.” Part of me wanted to agree with her.

“Hey Ms. Koroski!” Marcus was bored of throwing his empty Monster can into the recycling bin from across the room and decided to join in the fun. “Why are we reading this stupid stuff about African women?”

I knew I couldn’t ignore the question.

“Because, Marcus, I believe that women are actually important in the past and present,” I said tartly. “And I think you could take a lesson from their ability to organize a protest against their opposition.”

His friends snickered and Marcus looked momentarily taken aback at my response before turning sullen. “Women aren’t important,” he muttered.

It was a victory of sorts—a pyrrhic, temporary one. And that was the power of depression. It erased the rational distinctions that might have helped me recognize that it was just a bad start to the day. Under depression, those days were disasters that would never end. The lessons that fell flat seemed like the end of the world, and the wrong things I said were signs that I should never have become a teacher in the first place.

Alongside the struggles, teaching was a constant, one I badly needed. In the throes of depression, my mind had been my biggest obstacle. I couldn’t stop my thoughts tumbling down, one on top of the other, each more damning than the last. But between planning, grading, instructing, and directing, I had little time left for ruminating. When the students came in, I had to teach. I had no time to dwell on my own feelings. When a class was going on, I almost forgot about everything else. I encouraged, I coached, I corrected, I disciplined, all in a period’s work.

I remembered why I got into this field in the first place. I loved people, particularly teens. I loved interacting with them. I loved helping them learn and discover, and I loved watching them grow.

Much of their growth wasn’t for me. As a student teacher, I was temporary. Students knew it and used it to their advantage. It took a good two months before my better classes stopped complaining every time I gave them a reading assignment. First period never relented their fight. I couldn’t change the way the year began and I wasn’t even there to see it end. Any growth and learning I saw seemed fleeting, any appreciation from students rather minor.

I’d like to say they showered me with cards on my last day or lamented my leaving, but on the whole, they didn’t bat an eyelid when I announced I was done. I was an impermanent fixture of their education and a small part of their lives.

So I felt some satisfaction when the class clown looked up from his worksheet one day and said, very seriously, “You know, Ms. Koroski, you’re not that bad.”

For them, that was tantamount to a declaration of love.

In the years before I went into teaching, I wondered if I was good enough to be a teacher. In the months before student teaching, I worried about whether or not I could teach with depression. It never occurred to me that not only could I teach with depression, but that teaching would also make me less depressed.

It never occurred to me that the experience of depression would make me a better teacher.

There are no answers for dealing with depression. There is no right way. I cannot give solutions. All I know is what worked for me. I know that through learning the skills of mindfulness and learning to teach, I recovered. I became less volatile and less vulnerable. I became kinder, more dependable and more confident.

Yet I resented it for so long. I wished I wasn’t depressed. I dreamed that I wasn’t so anxious. I hated that I had to practice mindfulness to maintain my mental health. I wished I could return to the life that was easy and familiar – the life that was normal.

But I couldn’t get back to normal anymore. I didn’t survive that semester by living with depression. I wasn’t suffering from a disease. I was thriving in spite of depression. I was living through depression. After that, did I want to return to the easy and familiar? I wasn’t so sure anymore.

I never did save my camper that day. Sean did. But one night in November, I saved myself.

Colleagues ask about my day, about my first year of teaching. They listen, nod, and tell me not to get so stressed. But it doesn’t hurt when they say that. I nod, smile and laugh. They don’t see that my stress is a sign of how deeply I care. They don’t know that how I live now is the reason I’m still alive. But I know myself. I know how I survive: I teach with depression.

*********

Delve into more thoughtful stories in Sheriff Nottingham X: The Green Issue – available on Amazon!