Home I’ll Never Be by Ryan A. Lough

I ARRIVED IN TUSCALOOSA earlier this evening, by way of Birmingham. Tuesday night. My day began a country mile east of Atchafalaya, in the heart of Old Louisianne.

My shoe leather was worn thin, so I put my thumb out at first light, hoping for a lift to the nearest decent town with a warm place to eat and a bunkhouse to rest my bones.

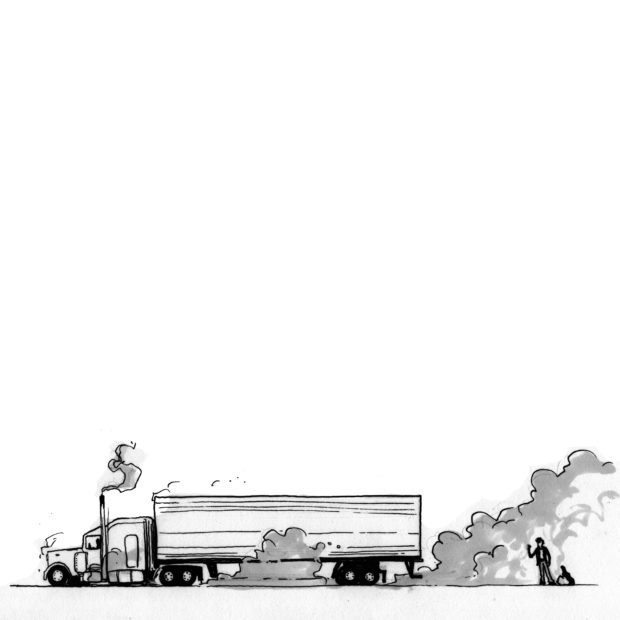

A brawny Peterbilt with a tire whine approached, and slowed to an inviting roll; its front right rubber grazed the gravel at the pavement’s edge. Air brakes sent dusty flecks of gold into the Dixie sunrise.

Good fortune, it seemed.

I hopped up on the passenger running board and got in the driver’s ear well enough for a ride. He told me he was heading through Alabama – up to Birmingham, then west to Tuscaloosa, before circling back through Jackson, Mississippi and back to his homeport of Baton Rouge. I needn’t return to Louisiana, I told him. I’d be getting out on the western edge of Tuscaloosa. I’m headed northwesterly. It’s a sliver off the desired route, but a cold rain was upon us. We shook on it, and in exchange, I was to buy his coffee and lunch. Deal. Any port in a storm. Off we went. Au revoir pour le moment, la Nouvelle-Orléans.

Now I’m perched on a curb in west Alabama with much more west ahead. Everything here is a crimson tide, the rain hasn’t let up, and the daylight has faded. My pockets are near empty – the Devil’s dance floor. I’ve packed light: my fiddle, a small duffel bag with a couple changes of clothing, a few books, my oyster gloves, the gold jewelry that she left behind – one with sparkling gems in it – and the final paycheck I received from old Lou Matherne last month, hours before he shuttered his business and sold his claim. Ain’t no oysters worth eating down here anymore – the water’s too warm, and the spill done mucked my livelihood, he said. Mine too.

I had been living on the Westbank, in Algiers, near Mr. Kern’s Mardi Gras World, on the banks of the Muddy Miss. In the morning, I smelled sewage and diesel that had traveled down from St Louis. By afternoon, I smelled the burning plastic and paint fumes wafted from Mr. Kern’s float factory. After the sun set, I smelled the night-blooming jasmine and gardenias from the neighbor’s yard, dancing with the nocturnal breeze that tugs the senses and beckons like a Storyville harlot after you’ve a had a few. Our creaky, drafty shotgun with raw wood siding was situated at the levee – we could see downtown New Orleans from the tilting front porch. We: my girl and I. That was until she up and left. Louella was her name. Disappeared without notice, only hints.

I had been out of work for the last three months, had to borrow quite a bit from Louella, and I couldn’t find a gig that could keep her satisfied. She often threatened to leave, and apparently she meant it. I came home last Friday evening, after pounding that sinking pavement, looking for a way to butter my bread, and the house was empty. Her belongings had been removed by a hurricane, though she did leave behind some jewelry. Trinkets and jewels that I bought her over the last two years, with extra cash I got from pulling up oysters, working overtime for old man Matherne. She smiled in an adorable way when I gave her these gifts. Her squinty eyes with smile lines conveyed genuine appreciation. An old-fashioned exchange, but we both found comfort in it. I like to think she had the decency to leave it behind for me to pawn and make some extra dough – the last bit of manna from her before she vanished like booze in a soup kitchen. I couldn’t afford to keep that leaky roof, so I left too.

***

Across the street from this curb is a pawn shop, and it appears to still be open. Prawn’s Pawn and Loan, the sign reads. To the right of the name, there is a poorly rendered icon of a jumbo shrimp wearing the Houndstooth fedora made famous by a man named Bear – an icon himself in these parts. The rain isn’t falling too hard at the moment. Aside from the diner down the street, and the Texaco across from the diner, Prawn’s is the only joint in the vicinity that had lights on. How welcoming.

I shuck her jewels and gold finery on the counter. The man, whom I’d like to think is known as Mr. Prawn, carefully examines the bounty. He’s a rather well fed man. He carefully examines me, too. To be expected, though – a road-weary rambler stumbling into a pawn shop with a pocketful of women’s jewelry doesn’t exactly discount the possibility of nefarious behavior, or the potential for questionable acquisition of such treasured items.

“These yours?”

“No sir, they belonged to the woman I love. Loved.”

“Mm-hmm. And you’ve gained possession of them how?”

“She returned them to me. I bought her these as gifts during the couple years we were together, and before she left, she gave them back. Ain’t got no choice but to hock ’em.”

“She gone?”

“She up and ran off.”

“She done runnoft?”

“Yessir. Didn’t even pen a Dear John.”

“By God. Sorry to hear that young fella. I’ll give you thirty dollars for the lot.”

“Can we make it a square fifty? Times is tough.”

“’Fraid not, son.”

“This is expensive jewelry, though.”

“They may sparkle, but them jewels aren’t in high demand here. Maybe you’ll have better luck elsewhere.”

He was about as expressive as a brick wall. He spoke very matter-of-factly, and his jaw exercised one large, circular chew of whatever was in his mouth, like a cow working over cud. His days were molasses.

I needed the money.

“Alrighty, thirty it is.”

“Then we have a deal. Initial here, here and here. And sign here.”

And just like that, I had a little more jingle in my step.

His handshake was firm. With a few crisp notes tucked into my slim billfold, I walked back out into the rain with my fiddle and duffel bag slung over my shoulder, hoofing it over to the diner for my first hot meal of the day.

There’s no denying that a roadside diner on the edge of town, with mellow lighting, foggy windows, and the smell of fresh coffee in the air, is a solid substitute for Mom’s kitchen. What really puts me over the top is when the waitress at the counter calls me sweetie, honey, sugar, or any other endearing title that warms the cockles of the heart, as she tends to my flipped mug and slides a menu in front of me. This is when I know that I’m in a place I belong. Home – for a meal, at least.

The air was warm and dry inside. A few patrons peppered throughout the booths didn’t look up as I entered and made my way to the empty counter. I’ve been here a hundred times in a hundred towns. A George Jones song filled out the limp air between the ambient chatter, clanks and clatters. The diner stools were bolted down and without backrests, so I spun my ass on the vinyl and into the attentive range of the waitress behind the counter, shedding my wet belongings into a mound at my feet.

“Hello there.”

“Howdy.” With a nod of my head, making eye contact. My mouth fell agape and my heart began to thump. Lily.

She was still prettier than a Spring flower, that’s for sure. I lost my words. Fumbled the ball. Slopped onto the floor. She stared at me, wide-eyed with heavy disbelief that made her lips quiver. I tried to collect myself, feeling cold shock fill my veins, and nausea reminiscent of my first day at sea. With a shallow, sharp inhale, her delicate voice broke the silence.

“Did you know I worked here?”

“N-no. No! Wow! This is a surprise!”

Neither of us had words to help the moment. Her flushed cheeks were adorable, and soft as a petal. I could sense her guard, and I began to wonder if I should leave. It had been a couple of years since we last had contact. We met a few winters back, while I was working as a deck hand in Galveston. She had finished high school the previous summer, and was working at a fish and beer joint down by the wharf, as a waitress. I would eat there every day after my shift, just to see her. We had a thing, and it blossomed. I was her first.

My young, wandering heart had every intention to marry her, someday down the line, once I saved up enough money. Work slowed as that summer approached, and by June, I was out of a job. I floundered for a couple weeks, but didn’t want her to know I was out of work. The skipper of the boat I was working on gave a call to a buddy of his in Louisiana, and landed me a job – full time – over in New Orleans. I had to go. I needed the work. I didn’t want to leave Lily behind, and I couldn’t take her with me – her father would not have approved. I promised her I would visit Galveston as often as possible, and would arrange for her to come visit me in New Orleans. After several months of being apart, our letters and phone calls grew more sporadic, and the last one she wrote me had a tone of impatience and discontent for my empty promises of travel. I just couldn’t afford it. We fell out of contact, and our lives became our own again. I loved her, though. Deeply. And now, seeing her again, I feel the tenderness in my heart, but it’s tamped down by a weight of guilt.

“You know what you want, or you need a couple minutes?”

“I’ll need a couple minutes on food, but coffee…”

“Ok, we’re gettin’ somewhere,” she said coyly. “You look like a drowned rat – soaked to the bone.”

This woman was fearlessly direct. Not quite hardened, but not far off. I broke her heart. She tilted her head when she poured my coffee. I caught her peeking up at me as my cup filled slowly.

“Yeah – the last time I drive with the top down in a storm.”

A joke any father would’ve made.

She didn’t respond. The cup filled, and she turned away with the pot, back to her counter duties. Lily of the Griddle. Stunned, she has me. And she seems out of place in here.

Eggs and sausage, side of toast? Biscuits and gravy; the old stand-by? Every diner menu has the expected items: Farmer’s Skillet, Denver Omelet, Short Stack with Eggs. But in these parts, you can generally find a place that prides themselves on their biscuits for soppin’, their country ham, and their creamy grits – none of that watered down shit. I was in luck. This was The Hen House, and not some truck-stop diner. It reminded me of that place in far West Nashville, the place with the barn out back, famous for their little biscuits. Can’t remember the name. But this joint, The Hen House, had it all: home-cooked breakfast for dinner.

My heart began skipping as she walked back toward me. Buck Owens wrote a song about this feeling, and by god, I could relate. Her blonde tendrils bounced on her shoulder, and her shoulders were back, confident. Slow motion in a cinema scene.

“Why are you here, if you didn’t know I was here?”

“I’ll have the country ham and eggs. Ahh, sorry – I’m a little road weary. I’m coming from Louisiana.”

Her casual chuckle let my taut spine loose.

“Well, you’re quite a ways from Louisiana. Isn’t that home?”

“Yes, ma’am. I suppose you could call it that.”

She leaned in over the counter. I maintained eye contact.

“Don’t call me ma’am.”

I shrunk a bit. She always was rough around the edges, and had a streak of “Don’t toy with me,” no matter who you were. I once watched her flip a table and knock out a customer with one swing, back at that fish joint in Galveston. He said something he shouldn’t have, and then grabbed something he shouldn’t have. She let him know he was out of his depth.

“Alrighty. Lily.”

Our eyes lingered together in a daze of curiosity. She broke it first.

“Country Ham and Eggs – how do you like your eggs?”

“Over medium.”

“Toast or biscuit?”

“Biscuit, please.”

“Grits, hash browns, or potatoes?”

“Your grits made with cream?”

“Yessir. They’re real good.”

“I’ll have grits.”

I could feel the road dirt in my premature crow’s feet as I smiled at her. She didn’t write any of that down.

“Really, what are you doing here?”

Her smile and curiosity plucked at the strings of my soaking wet heart. Chuckling under my breath, still nervously, I did my best to avoid the potential sinkhole that her question called into focus, so I diverted.

“I’m off to the West. Northwest, actually. Up Seattle way, I think. Maybe Alaska.”

“You think?”

“Reckon?”

“Ha!”

“I’ve never been there, and it seems like a decent spot to set up for a while. What are you doing in Tuscaloosa?”

“I’m in school now.”

The ice melted in my cup of water. She hollered my order to a cook, and carried on with her counter duties and sausage gravy affairs. I stirred my coffee, staring into the swirl. Thought about what it would be like to spend the evening with Lily. I suppose I’m a simple creature, really – I have few needs and a measurable amount of desires. She glanced over at me, repeatedly, as if she were Jane Goodall, and I was an ape; a well-kept distance, but an earnest profiling. The curiosity in her study intrigued me. It was nice to be out of the cold rain, and back in the company of Lily, as unexpected as it was.

Moments later, the kitchen bell rang, with ‘Order up’ cracking the air. She hurriedly set my food down in front of me, and turned away before I could respond with a thank you.

This was the first hot meal I’d had in what felt like a month of Sundays – as welcome as a fresh pair of socks after walking all day. Living on the road or as a transient for so many years turns you into a base creature, seeking the physical and visceral comforts that exist within the simplest and most mundane aspects of living – moments taken for granted by folks with busy jobs that live in the big cities. The Whiteshirts. Their gratification seems to arrive with financial gain, besting a colleague or vocational opponent, or being escorted to the front of the queue, bypassing the line. It’s the expected first-class treatment; the charlatan of bought happiness that gives way to mockery when looking back toward the steerage that lack the privilege. Us tramps and transients are free of this conceit – we’re content with warm chili on a snowy day working the prairie, a pillow when sleeping on the floor, the company of a beautiful lass when passing through town for a few days, stories of leaving and coming back, a lift to town when it’s raining buckets, egg yolks the size of saucers, and the warm smile of a pretty waitress in a diner where a cup of Maxwell House is still less than buck. Good to the last drop.

“How is it?”

She snapped me out of my daze, my mouth shoveled full.

“Damn good.” Crumbs of the biscuit crumbling off my lip; the ape, fumbling in front of Jane. She watched me eat for a few seconds and before I noticed, she turned away again and went about looking busy.

“Pardon me – may I have a warm-up on my coffee?”

“Yessir.”

“Don’t call me sir.”

She smiled and bit her lip, an intentional cue straight out of a movie. We looked each other in the eyes for what felt like minutes. I could feel my heart beating in my cheeks. I could see her heart beating through her blouse – the veins on the back of her hands were pulsating as they pressed palm down on the table. She leaned forward as if pushed by a breeze.

“Are you staying here in Tuscaloosa for a while?”

“I hadn’t planned on it, but then again, I don’t have many plans, other than to keep moving west. No schedule.”

“So you’re leaving this evening – keeping on?”

“I’m not sure yet. It’s getting late and the rain still hasn’t let up. I may need to find a motel and call it a night.”

A Hank Williams tune played, and his words made it well when we had none. She pursed her lips in thought, but did not speak. I couldn’t afford a hotel room – not with all the road ahead of me. I should leave and not make this into an ordeal. Why would I stay in Tuscaloosa? Sure, it’s damn unfathomable crossing paths with Lily here, after not seeing her for years, but this was not part of the plan.

“Wanna hang out a little? I finish up here in about a half hour.”

“You bet I do! Hhmm – yes. That sounds fine.”

Good god.

“Tell you what, you go across the street and buy us a couple cold ones, and I’ll take care of the ticket for this here meal.”

“Oh, you don’t have to…”

“Don’t you worry – go on ahead, finish up and get over there before the market closes.”

“Well, alright. Won’t do me no good to fuss with you.”

“Oh, and can you get some motor oil for my car – it leaks and I need to fill it up before I drive it again. I forgot to get it this morning.”

“You bet. Which car is yours?”

“That blue Ford on the edge of the parking lot. The one with a puddle under the engine.”

“Ah, I see. 10w-30.”

“That sounds about right.”

Happy to oblige, I scraped the last bit of food off the plate, sopped up the surface with the biscuit, and waltzed out to the Texaco. I noticed her smiling when I looked over my shoulder – the same smile she used to flash me at the fish joint in Galveston each time I had to depart. Time is relative.

The Texaco had a rack of motor oil outside. 10w-30 was on sale. The beer inside was not. My pocket was light, and would only get lighter with no work and more time spent away from the coast. I picked up a 6-pack of Dixie – old memories – and asked the sweet old lady behind the counter if she could cash my thirty-dollar check. I told her my story, briefly. Coincidentally enough, she was from New Orleans, but had left many years ago when her husband relocated for work. She agreed to help me out, with an almost maternal intent.

“You just sign it over to me. Here’s thirty dollars.”

“You’re very kind, ma’am. Can I bring you something from the diner?”

“No honey, save your money. Thank you, though. Happy Mardi Gras.”

“Yeah! Same to you!”

Oh, the guilt. I knew it’d be waiting for me around the corner. Sometimes you know it ain’t right but you do it anyway. As I left, I swiped two quarts of oil from the rack just outside the door as the door closing behind me obstructed her view. I wasn’t stealing from her – she was only an employee.

I popped the hood on the old Ford to check the oil and fill it as needed. These motions are something every country boy knows, and the smell is always the same. Brings about a sense of freedom and longing for the open road. I heard footsteps behind me…

“They let me out early.”

“Well, hello there, Ms. Lily.”

Something about a waitress smiling at me.

“I got you an extra quart.”

“Why, thank you. Wanna get outta here?”

“After you, darlin’.”

***

***

The ride to her house was quiet and awkward. We were separately consumed by our nerves and the anticipation. Felt like a blind date. I couldn’t think of what to say, or ask. Maybe I was thinking too much. She gripped the wheel tightly as she drove, eyes ahead the whole way home.

Her place is the smaller half of a mid-century duplex, near the university. Her presence is everywhere inside. This is her home, of sorts. I’ve never known her nest before – when we were together in Galveston, for those wild few months, she lived with her father. We would often stay at motels or find our way into some of the empty beach homes along the coast that she knew would stay empty for the time we needed. She was a local – she knew the homeowners that were coming and going. This new home of hers felt like Lily, but a Lily I didn’t know. A gentle paradise in foreign land.

“Make yourself at home. Pardon the mess.”

I looked around a bit after putting the six-pack in her refrigerator. No photos of another man. She obviously lived here alone.

“Play me a tune!”

“Oh yeah?”

“Yeah – I used to love it when you played for me back home.”

A faint sadness came alive in her face, and when I noticed, it flashed away. I sat at the table in her modest kitchen and played a Cajun tune I’d picked up in South Louisiana from the old man of a fellow deck hand – an old fiddle waltz. She smiled and pulled two beers from the fridge, twisting the caps off, waiting for me to finish playing before having a sip. I lifted my bottle in the air.

“Happy Mardi Gras!”

She laughed and toasted with me. The tension from the drive here was gone, and we were warming up to each other – feeling around for that sense of one another that we once knew, and we’d begun to find it. Straight into each other’s brains, no small talk. Brilliant conversation – this woman was beautifully intelligent and stunningly sexy. More than I remembered, actually. She’d grown up a bit, maybe a little more than me. After our second beer, she grew silent for a moment before looking into me with a force I hadn’t seen in years.

“You’re still as handsome and charming as I remember you.”

I started to respond, but she shushed me and pulled me up from my chair. We kissed a kiss for memory’s sake, and then another one for the sake of the moment, and then off we went into her bedroom. Our clothes quickly evaporated. Blind love. The evening was ours and ours alone.

***

“Why Tuscaloosa?”

“I needed a change, needed to get away from the Gulf Coast. And I wanted to go to college.”

“But why’d you pick Tuscaloosa?”

“Why are you heading west?”

We laid together in silence in her bed, naked as jaybirds, glow from a streetlight spilling into the darkness of her room through an unobstructed pane of glass. Stillness lingered outside in the heart of the night, like the uncertainty and loneliness that only a ramblin’ man knows.

“I’m going west because I need work, and things didn’t work out in Louisiana as I’d hoped they would. I would’ve come back to Galveston, but I wasn’t sure you’d want to see me again.”

“That’s bullshit.”

“No, it’s not. I figured since we fell out of contact – which was my fault, I’ll admit to that – you wouldn’t care to see me again years later, appearing from the past like a ghost.”

“Do you assume your way through life?”

“I’m not sure what you mean.”

“You missed a lot – you left a lot behind.”

“I wanted to marry you.”

“Oh my god, don’t say things like that.”

“I did!”

“Stop!”

She was genuinely upset with what I’d said.

“You can’t just fall off the map for years, then resurface and say those kinds of things so casually.”

She wrestled her naked body out from the twist we had knotted.

“I’m sorry – you’re right, I shouldn’t talk like that. It’s out of line. I’m sorry.”

“I’m tired.”

She turned her back to me, and her breathing changed to that of a withdrawn and relaxed state. She was actually trying to go to sleep. I caressed her back and legs, and soon enough, we were both fast asleep.

***

I awoke to her looking at me, laying with her head propped up on her hand.

“You still snore a lot.”

“Ha! Good morning to you, too. You still upset with me?”

“No.”

“Well, that’s good.”

I could sense she was in a mood by her eye contact and studious gaze upon me.

“You said you’re going west for work – taking a chance. Do you know anyone out there?”

“No, I don’t. But I’m pretty good at meeting people.”

“Why wouldn’t you go back to work with your father in Maryland?”

“That’s not in the cards.”

“Why not?”

“It just isn’t.”

“Well, why not?”

“Because it just isn’t.”

“I don’t understand – doesn’t he do what you do?”

“He used to.”

“Oh, he retired?”

“You can say that.”

“You’re so vague – you’re always so vague.”

Crickets for a minute or two.

“My father used to run a decent oyster harvesting operation, but he fell on hard times. He had to borrow money to stay afloat, but had a hard time paying that debt back – his business never picked up again. He borrowed from the kind of people you shouldn’t borrow from, and now he’s at the bottom of the Chesapeake, deep between the shoals, wearing cement shoes.”

“Good Heavens – that’s horrible! Are you being serious?”

Her eyes had genuine worry.

“Yes. I am. And now I can’t go back to Baltimore. My family name’s no good there.”

“Wow. I’m sorry to hear that. And your mother passed away when you were a kid, I remember that.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Don’t call me ma’am!”

The way she said that with light laughter was her way of trying to lighten the mood. She softly kissed my cheek and smiled at me with a tender compassion – the kind of smile that mothers give their children.

“I’m sorry to hear about your father.”

“Yeah, well…”

“Maybe one day you’ll have a family of your own, and you’ll find peace.”

This struck me as an odd thing to say, especially since she was getting out of bed, covering herself while she said it. She went out into the kitchen and her voice trailed.

“I have to leave here in a bit. You want coffee? I’m making some for myself.”

The shift in her demeanor and tone of voice was a clear indicator that this serendipitous meeting was about to come to an end, and our separate paths should continue along their individual routes. I shouldn’t resist this, because I didn’t deserve more of her time – I did fail to follow up on my promises to her in the past. I couldn’t expect her to drop her life that she’s made for herself and come running back into the arms of some transient pauper.

“Sure, I’ll have a cup.”

In the daylight, her place seemed quite different. There were many more things scattered around than I’d noticed. Mostly homework. The place looked almost in a state of disarray – the comings and goings of a hurried person strewn about. There were photos on the wall of the hallway going to the kitchen. Family photos, photos of Lily on the Texas coast – wall decorations that observant types come to expect in the humble abode of a Texas girl so far away from home. Reminders everywhere. At the end of the hall, in a little alcove built into the wall, like an altar, there were two photos: one of an infant girl, and another of Lily holding an infant girl. They were embossed with the Olan Mills gold stamp in the corner, and have nice frames around them. I pick up the one with Lily holding the girl, and bring it to her in the kitchen, my curiosity piqued.

“Who’s baby is this in the photo?”

She stiffened up and stood without turning to acknowledge me, facing the window that was above the sink. Early morning sun spilled in, and aquatic reflections on the wall from the birdbath just outside the window made little glints of dancing light appear on her shoulder.

She began to weep. I began to tremble with confusion that gave rise to a bizarre, intuitive fear. She was keeping something from me, and it was hurting her to speak of it, but that beast of burden was prying her mouth open from the inside, and was poised to lash out at me like a demon of past transgression hell-bent on inflicting misery. After a moment, she turned around with tears streaming down her face.

“She’s your daughter. Her name is Rose – after your mother.”

I had to take a seat. My breath vanished – dizziness, heart beating like thunder. The moment did not feel real. My mind flooded with questions, but Lily answered them before I could speak.

“She died at six months from sudden infant death syndrome. I found out I was pregnant a few months after you moved to New Orleans, and I had to keep it a secret from my father. He found out anyway, but didn’t allow me to tell you. I wrote you a letter, against my father’s wishes, but the letter came back with a return to sender stamp on it. I tried again, and again, and again, but they kept coming back. And it’s because you weren’t living at the address you gave to me.”

“I didn’t lie, I was…”

“You lied. I was a damn fool for not seeing it. I’ve had to deal with all of this entirely on my own.”

She paused to recollect. I was paralyzed.

“I had Rose, but she died in her sleep back in Galveston. And I didn’t know where you were in the world.”

She began to cry, and I couldn’t keep my own tears from flowing. I couldn’t breathe. The next few moments were heavier than lead. The room sank into an abyss that only the two of us would forever know. She stopped crying when she saw me begin to unravel, and she spoke.

“Your coffee is ready. I need to take a shower and get dressed. When I’m ready, I can take you to the bus station or wherever you need to go, but you can’t stay here.”

**********

Read more stunning stories in SN9: Fat Tuesday – available on Amazon!